In the early days of NEXUS many of our “instruments” were various found objects – things not originally designed to be used in musical contexts. At that time I particularly enjoyed browsing for unusual-sounding implements in hardware stores and kitchenware departments. During the 1970s many common household items were still manufactured using quite high-quality materials. Bundt cake pans, for example, originally were made of very thick and heavy cast aluminum, and produced a wonderful long-ringing sound when struck with a vibes mallet. They had a fantastic clear pitch and resonance not found in current ones, which are now made from thinner aluminum or other metal alloys.

In 1970 I bought a set of seven large graduated stainless-steel mixing bowls at the old Sibley’s department store in Rochester, NY. I spent quite some time testing all the bowls on display until I found the ones with the best sounds. They were far more substantial than the usual type available today, and had a marvelous ringing tone when resting upright on a padded surface. When inverted and played with vibes mallets, the flat bottoms produced a sharp metallic ping with a pronounced upward bend to the pitch, similar to some Chinese opera gongs. The mixing bowls became a favorite part of my improvisation setup, and I continued using them for many years.

During the later 1970s I began to find discarded fire alarm bells at flea markets and antique shops. These bells are still commonly in use as emergency signals, and are manufactured from heavy steel in a variety of sizes.

During the later 1970s I began to find discarded fire alarm bells at flea markets and antique shops. These bells are still commonly in use as emergency signals, and are manufactured from heavy steel in a variety of sizes.

Many of them produce a beautiful ringing sound when removed from their mounts and suspended freely. After some searching, I was able to assemble a graduated set of seven bells ranging in size from 6 to 10 inches in diameter.

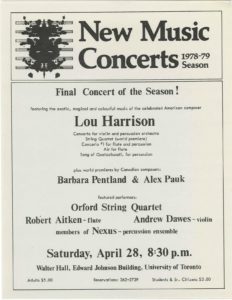

In 1979 the American composer Lou Harrison came to Toronto for a concert of his music presented by New Music Concerts. The program included his Concerto for Violin and Percussion Orchestra (1959), and Song of Quetzalcoatl (1941).

During rehearsals Lou and I discussed the sounds he intended for “suspended brake drums” and “muted brake drums”. Among other things, I was playing a part from Quetzalcoatl that calls for both types of brake drums in graduated sets of five. Many percussionists continue to use very heavy cast iron automobile brake drums, of the type commonly used in steel band “engine rooms”, for Harrison’s pieces, but Lou explained to me that these do not produce anything like the sounds he had in mind for his music.

Brake drum from 1962 Ford Galaxy

The brake drums used by his own early ensembles were designed for older models (1930s and 40s) of pick-up trucks, and were quite small and much thinner than more modern versions made for the very heavy cars of the 1950s and 60s.

Brake drums from 1932 Ford truck model BB

Lou said the brake drums he had in mind sounded more like bells or gongs, and so I suggested using five of my fire alarm bells as substitutes for suspended brake drums, and kulintang gongs from the Philippines in place of muted ones.

I arranged the instruments on a padded table top, and played everything with medium-hard vibraphone mallets. The fire alarm bells were inverted, with the open side facing up so they could ring freely. Alarm bells are quite heavy, and stayed firmly in place without the need for any special mounting. I played the kulintang by hitting them on the flat upper surfaces rather than on the buttons, which produced a muted, but still beautiful metallic quality. Lou was very happy with these sounds, and said they really captured the more delicate ringing character he had in mind.

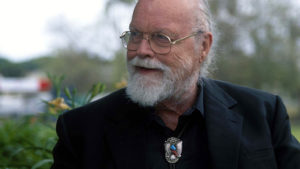

Lou Harrison (1917 – 2003)

I was at that concert , it was the first of many.