In 1989 Carnegie Hall announced a series of commissions to celebrate the hall’s 100th anniversary season in 1990/91. A former member of our management team, Costa Pilavachi, recommended NEXUS be the featured soloists in a new piece by Toru Takemitsu, to be premiered with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Seiji Ozawa. A concerto by Takemitsu had been on our wish list for a long time, and this opportunity was a dream come true.

I’ve written at some length in other articles about my personal experience with this event. I was shocked and somewhat dismayed when, six weeks before the premiere, I received the music for From me flows what you call Time and discovered my part was mainly for “Steel Drum (double lead pans)” (sic). The score showed a sounding range of two and one-half octaves from F# below middle C up to high C#. At that time I had only a vague idea about the different types of pans that comprise a steel band, and although I was generally familiar with the sound of the instruments, I had never owned any myself and certainly had no training or experience playing them.

Takemitsu had heard NEXUS perform his Rain Tree several times, and he also knew my keyboard abilities from numerous tours in Japan. I had been anticipating an elaborate vibraphone or marimba part in the new concerto, but in fact there was more written for pans than anything else, often played in tandem with vibes and a glockenspiel. Not only did I have to contend with a musical instrument I had no idea how to play, I was faced with learning an entirely unique invention: the steel pans-vibraphone-glockenspiel console.

My first reaction was panic, and the thought of backing out of the performance crossed my mind; however, I made one fortunate decision – I phoned a friend and colleague, Paul Ormandy, who is a fine percussionist and accomplished steel pan player. By sheer chance Paul had just returned to Toronto from Trinidad, and he had a brand new set of double tenors for sale. The pans had been made for him by Roland Harrigin, one of the best makers in the world, but they were configured with Phase II tuning, a pitch layout that Paul no longer wanted to use. Of course this made no difference to me – I was concerned only with having all the notes I needed to play my part – and so I bought the pans directly from the trunk of Paul’s car. They sounded great to me on first hearing, but it wasn’t until I spent more time with them, and had opportunities to compare their sound to other instruments, that I came to understand just how lucky I was to own them.

From the moment I took the pans back to my studio I was completely on my own. I had no teacher and no lesson books or instruction videos. In any case, given the severe time constraint for preparing the concerto, I had no time for study or practice of traditional technique and repertoire – I needed to get organized and learn the music. The first serious problem was how to configure the three principal instruments in my part, much of which is notated using three staves. At times I have to move rapidly among the instruments, often playing two of them simultaneously.

Standard steel drum stands, which hold the pans horizontally, could not be positioned close enough to the vibraphone and glockenspiel keyboards, so I constructed a rack system that allows the pans to be suspended vertically above the vibraphone, much like two gongs (an additional, third hole was drilled at the top of each pan, and a loop of plastic-coated wire threaded through it). Both instruments were stabilized at two other points to keep them from swinging around, and to provide some means for adjusting the vertical angles.

Standard steel drum stands, which hold the pans horizontally, could not be positioned close enough to the vibraphone and glockenspiel keyboards, so I constructed a rack system that allows the pans to be suspended vertically above the vibraphone, much like two gongs (an additional, third hole was drilled at the top of each pan, and a loop of plastic-coated wire threaded through it). Both instruments were stabilized at two other points to keep them from swinging around, and to provide some means for adjusting the vertical angles.

In relation to determining this suspension system, I also needed to decide on a right/left orientation for the two pans. Since I had no experience with double tenors, I based my decision on the part itself, and chose positions that facilitated sticking across the two pans as well as movement between them and the vibraphone. After learning the concerto, I continued to use the same positioning for all of the pan parts in pieces subsequently written for NEXUS and me. Some years later, following a concert at PASIC, I was informed by no less an authority than Andy Narell that my chosen setup was exactly backwards. He was amazed I could play anything that way.

Along with the new pans, Paul Ormandy had given me a pair of simple wooden pan sticks with standard latex rubber tips. In 1990 aluminum-shaft pan mallets were not yet in common use. Eventually I got a slightly more professional pair, also with wooden shafts.

I used these mallets for the premiere performance and for around a year thereafter. In 1991, during a short residency at the University of West Virginia, Phil Faini introduced me to the very inventive pan designer Ellie Mannette, who gave me a pair of his own aluminum-shaft mallets. Ellie’s sticks felt far superior in my hands, and produced a better and more easily controllable sound. They also had different thicknesses of latex on either end – a useful feature that allows for a change in articulation and timbre on the fly.

I used these mallets for the premiere performance and for around a year thereafter. In 1991, during a short residency at the University of West Virginia, Phil Faini introduced me to the very inventive pan designer Ellie Mannette, who gave me a pair of his own aluminum-shaft mallets. Ellie’s sticks felt far superior in my hands, and produced a better and more easily controllable sound. They also had different thicknesses of latex on either end – a useful feature that allows for a change in articulation and timbre on the fly.

I continued to use the Mannette sticks for several years until I began an association with Panyard, Inc. in 1995, at which time I changed to their somewhat larger and more sonorous mallets.

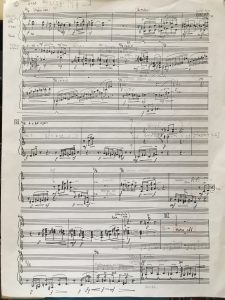

The next step in preparing the concerto was to copy, by hand, my entire part (this was before I joined the world of Finale and midi keyboards). Takemitsu’s publisher had provided lengthy percussion scores showing all five soloists, but I wanted a separate part with only the cues I needed from the orchestra and NEXUS, on as few pages as possible, and with no problematic page turns. Since the layout of pitches on steel drums, especially on double pans, is unlike any linear system I knew from standard keyboard instruments, I had to rely completely on muscle memory of spatial patterns in order to play my part. From initial rehearsals through the very first performances I played all of the passages involving pans by memory.

From me flows is a major work with a large and elaborate orchestration, and lasts around 35 minutes. NEXUS engaged a brilliant composer/pianist, John Hawkins, to create a piano reduction of the score so that we could rehearse with some idea of what the orchestra would be doing. Takemitsu himself attended a few of these preliminary sessions in Toronto, just before we packed up our gear and traveled to Boston for the first (and only!) real rehearsal with Ozawa and the orchestra. The next time we heard the actual orchestra accompaniment was during a run-through on stage the day of the premiere. As usual when new and delicate instruments were added to my inventory for NEXUS touring, I needed a strong and well-insulated road case for transport. Very often I have spent more on cases than the cost of the instruments that go in them, but fortunately in this instance I was able to re-purpose a trunk that had been made for something else. This case has carried my pans safely on dozens of trucks and planes for over 25 years.

Finally, on October 19, 1990 NEXUS premiered Takemitsu’s concerto in Carnegie Hall with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa conducting. The following day we traveled with the orchestra to Washington, D.C. where we gave the second performance on October 20 at the Kennedy Center. Although fraught with challenges, learning and performing this work was a fantastic adventure. NEXUS has played the piece more than 80 times with major orchestras all around the world, making it by far the most successful concerto work in our repertoire.

Part 2 of this article will describe my experiences with steel pans in the years following the Takemitsu concerto. Pans are featured in four additional major works composed for NEXUS: A Flute in the Kingdom of Drums and Bells (1994) by Michael Colgrass, Tallbrem Variations (1994) by Bruce Mather, Lullaby for Esmé (1997) by Robin Engelman, and Shadowman (2000) by R. Murray Schafer.

This is a fascinating and wonderful article! Thanks for posting this! What a treasure to read this! So much honest detail about every step of the way.

Many thanks! I will share this with the U of Toronto Steel Pan Ensemble.