NEXUS has gone through years of repertoire for solo percussion, ensemble percussion, band and orchestra with percussion, and percussion with chamber groups of all sizes. To this day, virtually every piece has presented problems to solve requiring the construction of instrument support stands or even of instruments themselves, not to mention special kinds of sticks and mallets.

Percussion parts are somewhat unique in that each piece of music has its own combination of instruments, its own requirements for placement within the setup, and its own issues with sticks and mallets. It would be analogous to having all of the the notes on a piano rearranged for every piece.

Solving the problems of instrument selection, setup and mallets – even before playing a single note – is in large part what percussionists do. The goal is not simply to play the notes, but in addition, to make the best possible sounds.

Listed below is a sampling of some the instruments and implements that were made in order to solve problems presented by the repertoire of NEXUS – problems for which there were no answers commercially available in music stores or catalogs.

Capatonus

NEXUS began as an improvisation ensemble performing on instruments, mostly non-Western percussion instruments – that each of us had collected, for which there was no existing repertoire. Each player would set up his own personal selection of bells, gongs, and drums, as well as found objects (salad bowls, glass beakers) and home made instruments. One such home made instrument was the Capatonus – a marimba with maple wood bars and plastic blueprint tube resonators. This marimba was originally given the whimsical name, “Orange Capatonus,” because of the orange-color caps that closed the ends of the tubes, but the caps faded in color over time and were then painted black.

One interesting feature of the Capatonus is its scale system, which was adopted in order to match pitches with a small toy xylophone. There are uneven intervals ranging from a minor-third to a quarter-tone as the scale is ascended.

Pedal Musical Saws

Another whimsical instrument was designed in order to have access to the sustained sound of a bowed musical saw without having to take the time to sit down and assume the normal saw-playing position, which could be very disruptive in a freeform improvisation. The pedal structure was designed to hold two saws while preserving the double-bends (“S” bends) in the saws that are needed to obtain the characteristic singing tone. By pressing the pedal, it was possible to raise the pitch while bowing with one hand, enabling the free hand to hold another instrument or mallet, all without the need to take a seat.

Flower Pot Drum

One of the first composed pieces played by Bob Becker and me was “Nara” by Warren Benson, the distinguished composer and mentor for NEXUS in its beginning. This piece was scored for small ceramic drums, and I decided early on to make my own.

For the bowls I used flowerpots set on a wooden base, The calfskin heads were tucked onto embroidery hoops that were tensioned by turnbuckles connected on one end to eyebolts in the wooden base, and on the other end to hoop claws made from bent coat hanger wire. The result was a set of three drums that had a beautiful ringing tone with the capability of adjustable pitch.

A few years later NEXUS decided to bring John Cage’s “Third Construction” into its repertoire. Each of the four percussion parts requires drums, and we made a decision to each have drums with a distinctive sound that would enable listeners to hear the difference between the four parts.

It seemed only natural for me to select the unique sound of the flower pot drums, which have served the “Third Construction” wonderfully though dozens of performances.

WindWater Machine

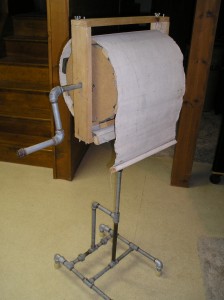

Another aspect of the NEXUS repertoire is music that is composed by NEXUS members themselves. One early example is a piece of mine, “Tides,” that was originally scored for ten players, but was later adapted for NEXUS. The piece requires both a waterfall machine and a wind machine. As with the theater ratchet (see previous posting – “Part 1”), these devices enabled the pre-electric world of theater and opera to create sound effects acoustically. A waterfall machine is simply a rotating wire-screen drum that contains marbles or pebbles. A wind machine is also a rotating drum with wooden slats that scrape against an overlying canvas sheet.

For “Tides” the waterfall and wind machines were combined into one rotating drum having both a wire-screen interior skin filled with marbles, and exterior wooden slats with an overlying canvas sheet. There was (and is) no such item to be found in any catalog.

Twirlytone

Musicians throughout history and throughout the world have always been fascinated by the sounds of birds. In travels around the world with NEXUS, we have seen and heard many types of devices intended to imitate bird calls – whistles, reed calls, wooden and slate scrapers, bellows devices, on-and-on. I have also collected dozens of such devices that have been put to good use in a piece titled, “The BIrds,” which has been performed many times and recorded by NEXUS.

In the mid 1970s, there was a major renovation of the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, and as part of that project, the old theater organ was completely removed – most of it ending up in a dumpster behind the Theatre. However, being very closely connected with the Theatre stage crew, I was given access to the organ’s echo chamber, which was located in a cove situated above the chandelier and above the suspended plaster ceiling of the Theatre. The echo chamber was only accessible by climbing a very high backstage wall ladder, and then gently stepping out onto a very long steel grate catwalk that ran above the Theatre ceiling.

Inside the chamber was a veritable treasure chest of organ pipes and percussion stops, all destined to be “dumpstered” unless heroically saved by caring musicians (ie. us). I managed to salvage about 25 small pipes and percussion effects, and while writing “The Birds” I had a brainstorm. By rotating a number of the small organ pipes over a hole through which I could blow air, I might be able to create the sound effect of a warbling bird. The devise was constructed, using a rubber tube to convey the air blown from my mouth to a small hole in the wood base over which the small pipes could be rotated.

The effect worked as intended, and the “Twirlytone” continues to be played whenever “The Birds” is performed.

Lujon (Loo-jon)

Sometimes, for whatever reason, the thought of making an instrument for an instrument just occurs out of thin air, and other times the idea happens as a result of seeing an existing instrument, either live or in a book. An example is the lujon. I saw a photo of one in the “Handbook of Percussion Instruments” by Karl Peinkofer and Fritz Tannigel (Schott, 1969, pp.59). It’s an instrument used in Luciano Berio’s “Circles.” Although the instrument pictured in the book appears to be chromatic (1-octave, C to C), in “Circles” the pitch seems to be relative (high/low) rather than specific.

After seeing the photo, and always being on the lookout for new sounds to use in NEXUS improvisations, I thought to myself, “I can make this.” The box was constructed of plywood with a 2-inch by 1-inch pine frame. The tongues were cut from a brass plate and bolted onto the frame. The sound is short and rather low-pitched, not unlike a marimbula.

Boobams

R. Murray Schafer is one of Canada’s most revered composers, and NEXUS has known and worked with him almost from the very beginning. In 2001, we premiered a work, “Shadowman,” composed by Schafer for NEXUS with the University of Toronto Symphony Orchestra conducted by Raffi Armenian. This was a theatrical piece, requiring the soloists to dress in costumes and to mime certain actions in performance.

My part was scored for 6 boobams, tuned G1 to E2, and when the part was given to me, I didn’t own any boobams. This was yet another example of the kind of situation faced by percussionists on a regular basis. I decided to construct the needed instruments.

The shells were made of 4-inch (I.D.) PVC pipe, which is available at any hardware store. Starting with the lowest pitch the pipe was first cut to an arbitrary length, and then shortened bit-by-bit until the G-nat. was reached. The same process continued for the remaining shells.

The most difficult parts to make were the counter hoops, so I just ordered a set of six 6-inch diameter bongo counter hoops from a commercial drum company. Along with the counter hoops I also ordered six 6-inch plastic bongo heads. Then I used the same kind of turnbuckle system that was used on my flower pot drums to attach the heads and hoops.

In 2005 NEXUS premiered “Rituals for Five Percussionists and Orchestra” by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. In the fourth movement of this piece my part calls for a number of improvised drum passages. I wanted my sound to be distinct from the other players, so I decided to use my six-drum set of boobams, which has worked very well in this piece for every performance since the premiere.

Antique Cymbal Support Structure

Also in the Zwilich “Rituals” player 3 must use a number of specifically-pitched small cymbals. In order to get the best sound, each cymbal should be suspended on a string or cord, but this system lets the cymbals swing freely, making them difficult to play in certain passages. Again, this is a typical problem faced by percussionists. One compromise solution is to mount each of the cymbals on a post, and if possible, construct a baseboard to have them all positioned relatively close together. In the Zwilich piece this solution worked very well. Almost every piece piece in the NEXUS repertoire has suggested – to me, at least – the construction of a wooden or polyfoam support structure, for small cymbals, woodblocks, or bells in order for me to be satisfied.

Eötvos Mallets

In 2007 NEXUS was invited to perform at the Ojai Festival in California. The featured composer that year was the Hungarian, Peter Eötvos, whose work, “Sonata per Sei,” scored for two pianos and percussion we would perform with the composer conducting.

As may have already been adequately demonstrated above, upon receiving a new part, there are usually a number of problems that have to be resolved. One problem that stood out initially in the “Sonata” was finding a way to use the best stick or mallet to get a good sound in passages that incorporated a diversity of instruments played together in rapid phrases that allowed little or no time for stick changes.

This kind of problem occurs regularly and it often requires that combination mallets be used. In the Eötvos “Sonata” I needed a combination snare drum stick/felt mallet/rasping stick in order to play one passage. Fortunately, combination mallets are starting to appear in catalogs and I actually found a pair of combination rasping stick/snare drum sticks. All that I needed to do was to make felt heads to attach onto the butt ends.

In one of the rehearsals Eötvos came back into my setup to check these combo-sticks out and following his look of inquisitiveness, he gave me a nod of understanding along with a gentle smile.

WaterGong Machine

As this is being written I am once again involved in solving a number of problems for a new work to be performed and recorded by NEXUS in a few months. As soon as I looked at my part, I realized that I would have to build a device to simplify the playing of a water gong. Normally, the player has to pick up and grip the gong in one hand, and then use that same hand to lower and raise the gong into a large tub of water, causing the gong’s pitch to be altered.

It occurred to me that I would prefer to not have to pick up a gong and lower it into a tub of water while striking it, and then set it down again. So I designed a pedal-operated water gong machine. The gong is suspended on a rail that can be lowered into a small water container simply by pressing on a foot pedal, leaving the hands completely free, so there is no need to put down mallets and then pick up the gong, etc.

I hope the examples presented here and in Part 1 will convey some sense of the open ended nature of performing on percussion instruments. In music making, there always is – and should always be – plenty of room to make individual statements. After all, making music is not a science; it’s an art.